Reparations for slavery: A road map

By

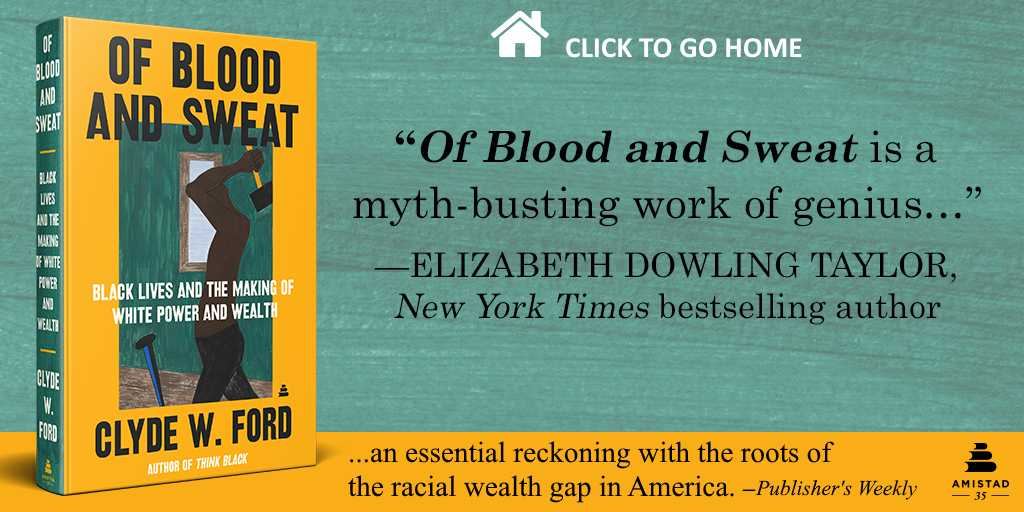

Clyde W. Ford

Special to The Seattle Times

The California state task force on reparations for Black residents voted on March 22 to limit eligibility to individuals whose lineage could be traced to enslavement in America. While this first-in-the-nation task force hotly debated the issue, more important is that it was impaneled by Gov. Gavin Newsome to study and develop reparation proposals. While many look toward California, awaiting its findings and conclusions, Gov. Jay Inslee, who’s been out in front on many issues of racial equity, should not wait. He should impanel a similar reparations task force, with similar objectives in Washington state.

Reparations to Black people, to be sure, are contentious. Opponents voice several issues. If my family never held people enslaved, if they came to this country after the Civil War, I have no responsibility for what happened during slavery, and I should bear no responsibility for paying reparations. Anyway, how do you compute what’s owed to the descendants of the enslaved? And how would reparations get paid out?

While the California task force grapples with similar questions, Washington state actually has experience paying reparations that might prove useful. During World War II, the Puyallup Fairgrounds (now the Washington state fairgrounds) was used as an incarceration camp, called Camp Harmony, for Japanese Americans rounded up and imprisoned under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066. After the war, and a long period of lobbying, Congress passed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, signed by President Ronald Reagan, which granted each surviving internee $20,000 in reparations.

But five years before this federal law, the Washington state Legislature passed a law, titled “Reparations to State Employees Terminated During World War II.” The 1983 law reads, in part, “[t[he dismissal or termination of various state employees during World War II resulted from the promulgation of federal Executive Order 9066 which was based mainly on fear and suspicion rather than on factual justification. It is fair and just that reparations be made to those employees.” The law, revised and refined over the years, specified those eligible for reparations, how they should submit a claim, and how much they should be paid.

The amount paid to the incarcerated was minimal — $5,000 at most. But the fact that the state, and the nation, recognized the undeserved harm done to Japanese Americans, then took steps to redress that harm through paying reparations, means that something similar can, and should, be done for Black Americans. It also means that if Washington state was a leader in reparations then, it can be a leader in reparations now.

When it comes to reparations for Black Americans, what many do not recognize is that it doesn’t matter whether your family’s forefathers held enslaved people, or came here after slavery was abolished. If you have ever opened a bank account, used a credit card, purchased a car or the insurance required for it; if you’ve ever bought a home and had a mortgage, or invested in the stock market, then you have directly benefitted from institutions created by the labor, and sometimes the bodies, of enslaved men and women.

J.P. Morgan, Wells Fargo, Citibank. Every major banking institution we know and use today was built by acquiring smaller banks, many from the South that held enslaved men and women as collateral for mortgages and other debts. The business of pledging the enslaved individuals one held as collateral for the debt one owed was used on several occasions by Thomas Jefferson to forestall the debt he owed to his European creditors. Something similar happened with insurance companies. These big companies that issue business, car and home insurance today grew into the behemoths they are by issuing slave insurance in the 19th century.

Even though this happened long ago, it affects us in this state today. Because of racism in banking, a process called redlining developed in which people in certain areas of a city, mostly Black people and those of color, were either prevented from obtaining mortgages, or saw sky-high interest rates that placed homeownership out of their reach. A recent map published in The Seattle Times shows that formerly redlined areas in Seattle are strongly correlated with worse air quality and therefore with poorer health outcomes. Such consequences are lasting and profound.

Even sadder is that a plan for Black peoples’ reparations was actually approved by President Abraham Lincoln at the end of the Civil War. Under an order from General William T. Sherman, called Special Field Orders No. 15, popularly known as “40 acres and a mule,” 400,000 acres of land was taken from Southern slaveholders for redistribution to the formerly enslaved. The amount of land for redistribution was soon increased to 900,000 acres, almost all of it rich coastal farmland from northern Florida to South Carolina. Before Lincoln’s assassination, 40,000 Black families had applied for and received tracts of this land to farm on. After Lincoln’s assassination, Special Field Orders No. 15 was rescinded by President Andrew Johnson. The land already redistributed was taken back and all of the land returned to the former slaveholders.

Which brings me to a formula for national reparations. Congress should follow through on the original reparation plan. The map of those 900,000 acres is well-known. The current value of the land fairly easily computed. That’s the figure with which to begin a discussion of reparations. And Washington state, with laws already on the books about determining eligibility, and filing claims for reparations, should be a leader in this process, showing the rest of the nation how it can be done.

Payout of reparation should be up for discussion. Land grants are probably out. But that leaves payments, or college tuition credit, tax breaks or a host of other measures possible.

And if Gov. Inslee appoints a commission to study reparations, he should also do what President Reagan did upon signing the Civil Liberties Act of 1988: Inslee should apologize for slavery, if not on behalf of the nation, at least on behalf of Washington state, and how the legacy of slavery advantaged some state residents, while disadvantaging others, simply on the basis of race.

This article first appeared as an op-ed in the Seattle Times