I never imagined that being a Black author could put me in harm's way

In recent years, the police have been called on Black people for ridiculously ordinary things — birding while Black, shopping while Black, golfing (too slowly) while Black, riding in a car with a white grandmother while Black, delivering newspapers while Black, even trying to cash a paycheck while Black.

Writing while Black is now putting authors at risk. Our books — fiction and nonfiction — are being banned as part of a conservative movement to quash teaching and the discussion of racism in America. With a “hate the book, hate the writer” ethos taking hold, suddenly, threats are being made against us.

Never could I have imagined that being an author might place me in harm’s way. No writer should face danger for reporting on historical truths or writing fictional accounts that tell the stories of historically marginalized communities. Yet those of us writing while Black often do.

Dozens of Black authors have had their books pulled from school libraries under the pretext that we’re teaching “critical race theory,” which can be simply defined as offering an intellectual framework to discuss how systemic racism in America was consciously created and, therefore, needs to be consciously dismantled.

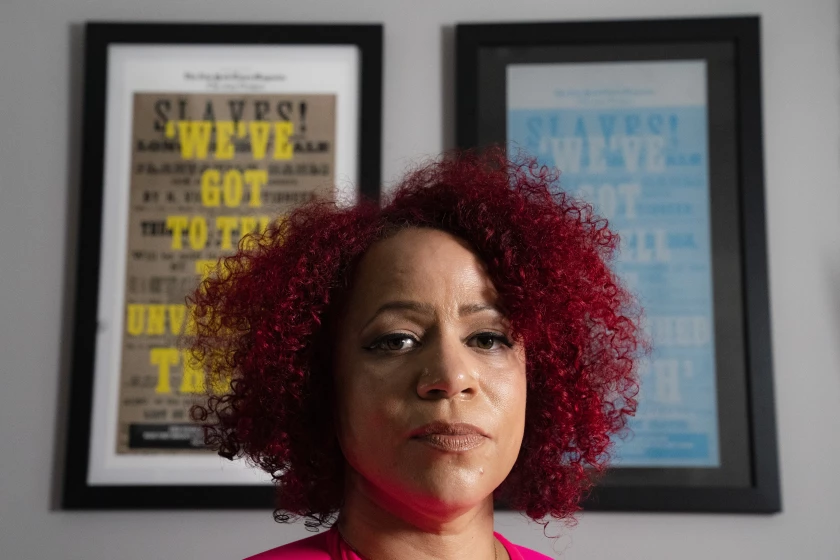

Nikole Hannah-Jones, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of “The 1619 Project,” was targeted by the Trump White House, was second-guessed by historians and was racially harassed and received death threats for her examination of the history of racism in America. The backlash was led by Republicans who used fears of critical race theory as a cudgel in an attempt to advance their political aspirations.

As others have picked up this weapon, the theory has become the basis for a chilling condemnation of most any discussion of race, racism or antiracism in America. And it has led to more book banning. The American Library Assn. reported more than 270 books were subject to censorship attempts in 2020.

One of the most banned books is “All American Boys,” a young adult novel by Jason Reynolds, who is Black, and Brendan Kiely, who is white. Through the perspective of two high school classmates — one Black, one white — it tells the story of a Black child killed by a police beating. The authors have said they see the book as a jumping-off point for kids who want to discuss race.

Last fall, Texas state Rep. Matt Krause, a Republican, released a list of 850 books he claims “make students feel discomfort” because they are about race and sexuality. One San Antonio school removed more than 400 books that were on his list. Among them were Mikki Kendall’s “Hood Feminism,” about feminism’s failure to consider the challenges women of color face, and Kalynn Bayron’s novel “Cinderella Is Dead,” which reimagines the fairy tale from the point of view of a Black queer teen.

In Florida, Gov. Ron DeSantis has pushed a bill limiting how schools and corporations can teach about racism. It would prohibit lessons or trainings that cause individuals to “feel discomfort” by implying that they bear responsibility for actions committed by their ancestors or other members of the same race and gender. More than 30 other states are pursuing similar measures.

So this is where we are? Books by Black authors are being banned — and legislation is suppressing discussion of race in the classroom — based on the absurd notion that it is possible to legislate and control how reading and discussion make someone feel?

These bills fail to recognize that while individuals may bear no responsibility for the actions of their ancestors, or members of the same race and gender, they still reap rewards from these actions — whether that means lower insurance premiums, better employment opportunities or greater familial wealth.

It’s a reflection of a racial wealth gap in America that has little to do with how hard a person strives and everything to do with the history of racism in this country. In our work, many Black writers attempt to point this out, and we’re being castigated for it.

If someone learns from one of my books that Thomas Jefferson used his slaves as collateral against his debt, and that causes the reader discomfort, then the use of my book may now violate the law in some states.

But violating state law while reading is not what concerns me. It’s violence — and the concern for the safety of authors — that does.

Harriett Beecher Stowe, a white author, reportedly received the severed ear of a slave in the mail as a warning against her anti-slavery stance in “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” Legendary Black journalist Ida B. Wells was driven out of Memphis after she reported on lynching in the Jim Crow South of the late 1800s.

Hitler’s Third Reich banned and burned books in the 1930s by Jewish authors and books proscribed as “un-German.” Mao Zedong’s China censored and burned anti-Communist and anti-Maoist books in the 1960s and 1970s during the brutal crackdown known as the Cultural Revolution. Al Qaeda insurgents in Mali torched rare historical works in 2013 in the ancient university city of Timbuktu. In 2015, ISIS militants burned more than 100,000 rare manuscripts and documents in Mosul, Iraq.

And in mid-March, former President Trump called on supporters to “lay down their very lives” to prevent critical race theory from being taught in schools. Trump’s comments should not be taken lightly. We all know what happened when he urged a throng of supporters to take action on Jan. 6, 2021.

When an ex-president calls for followers to fight to the death against ideas espoused by Black authors, I can’t help but worry we’re witnessing the beginnings of outright violence against those authors, and their books, here in America.

Truth is a powerful weapon. As Black authors we must have the courage to continue wielding it while telling the truth about America’s racist past.

This article original appeared as an op-ed in the LA Times.